This is the final blog posting in a series of 6 focussing on the architecture of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. In this posting I will consider the placement of the organ and choir, before offering some general thoughts and conclusions to the series of blog posts.

The architect, Frederick Gibberd placed the choir behind the altar. This placement both allowed the choir to be part of the liturgical ministries and ensured the continuity of the circular shape, whilst not running the risk of disenfranchising members of the congregation. The positioning of the organ was a functional requirement, in that it needed to be placed in a position from which it could speak freely into the space of the Cathedral. Naturally then, the choir was placed directly in front of the organ pipes so that all musical leadership is provided form the same place.

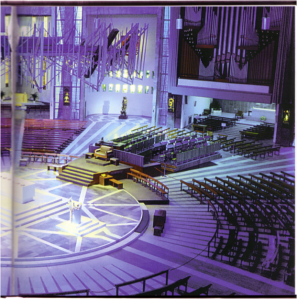

Some experimentation has taken place regarding the direction and placement of the choir since the building was completed. Gibberd designed a raised choir enclosure, which had all singers facing directly towards the high altar (as can be seen in the picture below from the consecration of the Cathedral.)

Whilst this was a suitable arrangement for Mass, it was not at all effective for the choral celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours, in particular sung Vespers. Experimentation led to the choir enclosure being removed, and choir stalls influenced by Anglican Cathedrals being placed in front of the organ case.

Conclusion

One wonders, had the Metropolitan Cathedral been built a decade later that it actually was, would it have been a different building with new liturgical principals? Whilst the placing of the altar in the midst of the people was a bold and innovative move, it does somewhat preclude adapting the building today. Whilst its usage for large diocesan occasions is obvious, does it serve smaller scale gatherings as effectively?

Gibberd himself expressed a hope that the building would be adapted and grown upon as was necessary in the future. Positive developments in this respect have been the majestic artwork that covers many of the walls in the cathedral that depict both saints and occasions that live strongly in the memory of the cathedral community. Noting the slow speed with which the liturgical movement took a hold in England one doubts whether building ten years later would have strongly influenced the design. It is striking that after winning the competition, Gibberd said ‘I have only the slightest knowledge of the new Liturgical Movement.’

One suspect that the members of the cathedral committee, and to a lesser extent, Archbishop Heenan, should be credited with the innovative liturgical design, and the decision to not place certain permanent items as the ambo and cathedra. Medieval cathedrals often illustrated the power and wealth of a city, displaying monumentality in both conception and material. However, these buildings rarely were/ are useful in a liturgical sense. Liverpool however should be proud, in possessing a Cathedral that illustrates both stature and beauty, sitting prominently on the skyline, whilst at the same time fulfilling a truly liturgical role as the center of Roman Catholic worship in the north of England.